What is “popular”? Popular is not fame or celebrity. Popular is not the products of mass culture. Popular is not pop. Popular is not the art of the people, nor the identity of the country, nor the symbols of the nation. The popular is not the product of the proletariat or the craftsmanship of the working classes. The popular is not folklore. The popular is not clichés or tourist souvenirs. The popular is not visual candy, one-euro merchandise, advertising royalties. Popular is somewhere in-between all of that, underneath all that, yet something different. popular is an exhibition and an investigation – showing is a form of knowledge – that aims to answer this question.

The popular is a form of imagination, often words, images and things, created through gestures, actions and celebrations, in many different ways. The popular has a performative, plastic, shifting nature, always metamorphosing, closer to ritual than monument, liturgy devoid of theology.

popular is based on a strong interpretation. Human groups, specific life-forms, possessing no political representation of their own, strongly develop their symbolic representation. This has happened historically; since the birth of the people, since the political revolutions of the late eighteenth century, it was precisely in the imagination of the peasant populace and the remotest areas of the republics where what we know as popular began to take shape. Specifically, in the most meagrely represented groups in political terms, because nation-states were strongly linked to the cities, the great urban metropolises. If we think, for instance, of how Afro-descendent imagery, while Black people were still slaves, became commonplace ways to represent the United States, Brazil or Cuba. Or, if we think of how the gypsies in Spain – but also in Hungary or pre-Soviet Russia – always politically excluded – embody the clichés of the nation – Carmen, flamenco and bullfighting – we might understand what we are talking about.

The formula is certainly not a simple one. For example, we know that in art, the categories of representation and participation cannot be completely separated. The task of precisely identifying human groups with a symbolic surplus is not only difficult work; it also does not necessarily involved submitting an archive – the IVAM archive, in this case – to a police-type gaze, an exercise of finger-pointing. The history of social emancipations gives us some idea of which human groups have managed to achieve political representation over the past centuries. The Industrial Revolution, the American and French Revolutions, the feminist revolution, are all added fields on which to focus our attention. If we look at Valencia in the twenty-first century we can see how the proletariat, women and LGTBI, in some way, but also Latin American, Arabic or African migrants in other ways, run through the imagination of what we call popular.

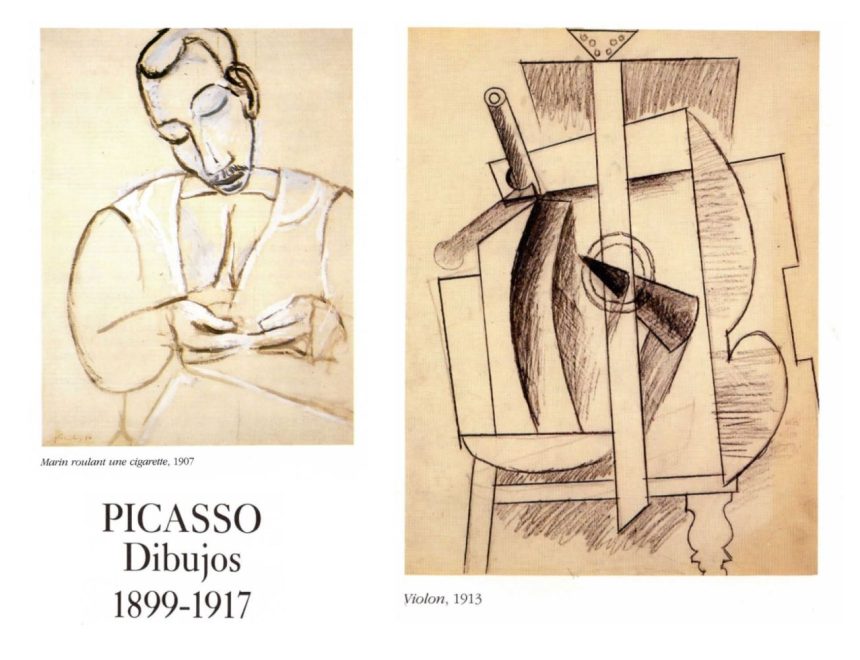

popular works with the IVAM’s rich collection broadening the focus on certain aspects – music, for example –, shining a light on many aspects of the collection – the imaginary of the working classes – and highlighting absences – the Afro-descendant imagination, for example. popular is a spilling out of the IVAM archive, like a feast for the gaze, with new lines drawn between the pieces – for instance, el Niño de Elche has made songs based on 15 items in the collection – genealogically overflowing – overflowing is another feature of the popular – the framework of what modern art means, but also attempting to set clear guidelines for interpretation, a little like Juan de Mairena’s Popular School of Superior Wisdom, in the words of our old friend Antonio Machado.

Activities popular

![[DOSMILVINT-I-U] [DOSMILVINT-I-TRES] = 1 encuentro](https://ivam.es/wp-content/uploads/exposiciones/programa-de-art-i-context-exposicion-proyecto-2021-2023/230608_SEC_DOSMILVINT_01-377x277.jpg)