Collection Treasures of Taino Art

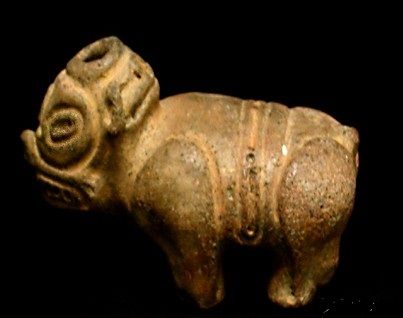

* * * The first section, Guayacán, introduces the world of the Taínos as a social group and as a culture. It takes its name from a tree that is renowned for its hardness, as a way of indicating the enduring nature of a culture that has succeeded in avoiding extermination, overcoming unjustified oblivion and celebrating its existence with a beautiful and enduring heritage. This meaning is conveyed to the visitor by the imposing figure of the Cemí de la Cohoba, a marvellous object loaned for the purposes of this exhibition by the Museo Arqueológico de Altos de Chavón, and by five other emblematic works of Taíno culture, extraordinary examples of the skills used by the Taínos to create their art and the materials that they employed: clay, bone, shell, stone and wood. This section is complemented by graphic material that provides information about the Taínos, their history, their migratory movements and their culture, and also by works of contemporary art that have very clear references to Taíno culture and by pieces of neo-Taíno craftwork created by modern Dominican artists and craftsmen with the conscious aim of reviving and celebrating the memory of the Taínos. In this way the first section seeks to show that the contemplation of the marvellous objects displayed in the entire exhibition will suggest a continuing connection with the present. * * * The second section, Huracán (Hurricane), shows the searching and profound dialogue that the Taínos engaged in with their environment in their attempt to penetrate the secrets of a world beset with threats and possibilities. It does so with a selection of implements that the Taínos made in order to work on their natural environment or to represent it in many ways, exhibited here with an audio-visual presentation that recreates the world of the mangrove (an important setting for Taíno habitation) and hurricanes, which together embody the principles that balanced the Taíno cultural imagination: calm and chaos. The significances and symbolism associated with nature provided the basis for the physical and spiritual creations of Taíno culture, which accumulated enormous wisdom in this fundamental aspect of life. Their “eco-knowledge” was so extensive and important that it proved decisive in enabling other groups of humans (mainly Europeans and Africans) to learn how to live in the territories of what is now the Caribbean. It is no accident that the contemporary Spanish language used in the Antilles and elsewhere has preserved many Taíno words connected with nature and work, some of which are reproduced on the walls of this section and the next one. * * * The third section is based on objects made by the Taínos in order to produce goods for consumption. Despite their utilitarian nature, these objects are very elaborate in terms of style and design. This section has been given the name Conuco, a word that the members of this aboriginal social group used to designate the area where they sowed their crops, presented in this curatorial discourse by means of drawings made during the colonial period. These drawings are contrasted with photographs of agricultural work in the Dominican countryside in the twentieth century in order to emphasise how Taíno ways of producing things have survived in life in the Caribbean. For the same reason, this section includes a cibucán, an object used by present-day indigenous peoples in Amazonia to press cassava root and make cassava bread, as the Taínos used to do. It is accompanied by implements currently employed in the production, sale and consumption of cassava in the Dominican Republic, and by contemporary pictures of the production process which show the survival of one of the most important manufactured commodities in the Taíno world. The present high levels of consumption of cassava throughout the Dominican Republic and the almost invariable way of processing it provide concrete examples of the enduring nature of Taíno culture. * * * Cemíes y cohoba, the fourth section of the exhibition, focuses on objects that the Taínos made for their ritual practices. This is functional art that displays a masterly combination of technology, creativity, religious beliefs and aspects of their social hierarchy. In order to provide a balanced understanding of this art derived from animist practices, the first part of this section shows an impressive selection of cemíes made by the Taínos to represent their gods, together with objects in the form of amulets with which they sought to obtain protection from those deities. The second part of this section sets out to show some of the practices by which the Taínos developed their beliefs. Examples are seen in the projection of pictures of stone carvings, images that the Taínos carved on stones that marked out their ceremonial places, and in the representations of various Taíno funerals that show the ways in which they buried their dead. The last part of this section presents the cohoba ritual and the objects associated with it. This ritual was used by chiefs and priests to go into a trance after inhaling hallucinogenic powder and purging themselves by ritual vomiting. This mysterious aspect is complemented by projections of pictographs that the Taínos drew on cave walls to worship their pantheon of gods. * * * The fifth section, Batey y bohíos (Native Settlement and Huts), is devoted to the social dynamics of the Taínos and their domestic life. It shows period prints of Taíno homes together with photographs of Dominican peasant houses taken in the twentieth century, and by comparing these pictures it is possible to identify the use of building materials, forms and techniques inherited from the pre-Columbian indigenous peoples. These pictures are accompanied by a varied selection of objects made by the Taínos as instruments with which to support their social activities, many of which had a strong symbolic meaning that converted them into representations of social power and hierarchy. Part of this last section is covered by a hanging panoramic photograph representing a roof made of palm leaves, such as might be seen in a chief’s house. To strengthen the connection linking these social practices and all their accompanying imagery with present-day domestic life, this section concludes with a selection of items of basketwork, pottery, etc. made by present-day Dominican craft workers who continue using Taíno forms and techniques in their work. There is also an altar indicative of the religiousness of modern Dominican people, which includes objects from Taíno rituals resemanticised by the new beliefs, together with other items of Hispanic or African origin. * * * Tesoros del arte taíno ranges from relationships with nature to the production of consumer products, and from there to ritual practices and domestic life, presenting a survey that seeks to establish a discourse highlighting the importance of the values attained by the Taínos and to show the delicate articulation which that human group achieved with their manifestations of social life and their expressions of creativity, which, despite all the odds, have come down to us to offer a dialogue with the present.