Ben Nicholson

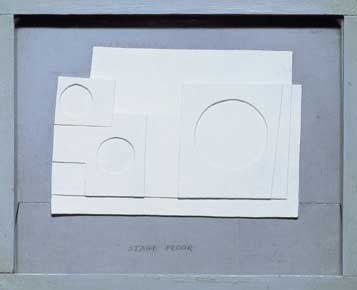

In the first half of the twentieth century Britain produced a small number of artists of truly international significance but none more so than the triumvirate of Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson. These three artists above all others were responsible for establishing Britain as one of the centres for modern art. However, while all three were leading practitioners Nicholson was the driving force. Ben Nicholson was born in 1894, the son of the painters William and Mabel Nicholson. Brought up in an artistic family, he fairly soon rejected the stylish but, for him, outmoded realism of his father in favour of a more modernist outlook. After marriage in 1920, Nicholson and his wife Winifred, herself a painter, spent the winters in Lugano and the summers in Cumberland, engaging in a period of fast and furious experiment in painting styles. On their way to and from England they would visit Paris to see the latest exhibitions. There they were able to see at first hand the work of Derain, Picasso, Braque and Cézanne as well as the paintings of the Italian Primitives. Nicholson gradually created his own post-cubist idiom exemplified in still lifes where forms were presented as simplified shapes within a shallow, flattened space. Still life was as much a vehicle for experimentation with pictorial language as a theme that evoked his inheritance and social surroundings. In London Nicholson became the chairman of the Seven and Five exhibiting society and, as his interest in abstraction increased, he transformed the society into one devoted solely to modernist abstraction. In 1932, after he had separated from Winifred Nicholson and began a relationship with Barbara Hepworth, Nicholson divided his time between London and Paris, where Winifred lived with their three children. In Paris he made contact not only with Braque, Picasso, Brancusi and Giacometti but also with the leading practitioners of abstraction, Mondrian, Hélion, Gabo, Herbin, Arp and Calder. He particularly admired the work of Miró and Calder whose disc shapes became an important element of his vocabulary. While in the early thirties Nicholson’s work was poised delicately between Surrealism and abstraction, by 1934, after the making of the first relief carvings, Nicholson rejected Surrealism in favour of geometric abstraction, albeit based upon an understanding of still life. His membership of Unit One in 1934, where artists from both camps congregated, was short lived and he adopted an uncompromising attitude towards all art other than geometric abstraction. He provided British colleagues with introductions to artists in Paris and was one of the forces behind the founding of the magazine Axis, the exhibition Abstract and Concrete held in 1935 and the magazine Circle, published in 1937 to promote what he and his co-editors, the architect Leslie Martin and the sculptor Naum Gabo, called the Constructive movement. Nicholson’s white reliefs, which were one of the high points of pre-war modernism, were expressive of the taste for clean design and purification. They were utopian statements in a period of increasing political anxiety, an urban expression much admired by architects and perfectly in tune with the prevailing aesthetic for buildings flooded with light, in which glass became a significant building element. The outbreak of war had a damaging effect on the advance of modernism and artists were scattered far and wide seeking refuge from the Blitz. While for a brief period refugee artists and architects had settled in London, many now continued their journeys westwards to the United States. Nicholson and Hepworth, by then married, moved to Cornwall, eventually taking up residence near St Ives. Cornwall had an immediate impact on Nicholson’s art. He not only began to paint landscapes but the range of colours he employed in his abstract paintings and reliefs reflected the bright light and the earth colours of the Cornish peninsula. After the deprivations of the war years and enforced isolation, Nicholson emerged triumphantly in the 1950s winning a succession international prizes for his highly acclaimed late Cubist paintings, in which his interest in still life and landscape achieved perfect harmony. If still life was the dominant interest in the 1950s, after he moved to Lugano in 1958 with his third wife Felicitas Vogler, he placed greater emphasis on relief carving, producing a series of magnificent works based on his appreciation not only of the surrounding mountains but of megaliths in Brittany and the buildings of ancient Greece. These interests formed the basis for a series of magnificent reliefs carved and painted in the mid 1960s. In 1971 Nicholson returned to England. His late works display a freedom of brushwork not previously encountered, which subverted the geometry and sharp lines of his relief carvings. He spent his final years in London where he died in 1982. This retrospective exhibition is the first to be held in Spain since 1987 and comes at a time when artists and art-historians are reassessing the modernist movement. Selected by Jeremy Lewison, Director of Collections at Tate and a world authority on Nicholson, it will present a full range of Nicholson’s work, while emphasising three key periods in his art: the 1930s, the mid 1950s and the mid 1960s. The exhibition will consist of more than 50 paintings, reliefs and objects including the magnificent, recently restored 1951 (mural) painted for the 1951 Festival of Britain, now in the Tate collection. It has never been seen outside Britain before and for over fifty years has been lost from public view. In addition to a large group of works from the Tate collection, the exhibition will include loans from many public museums and galleries, the Arts Council of England, the British Council and many private collections.