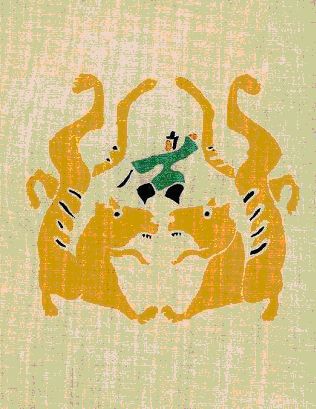

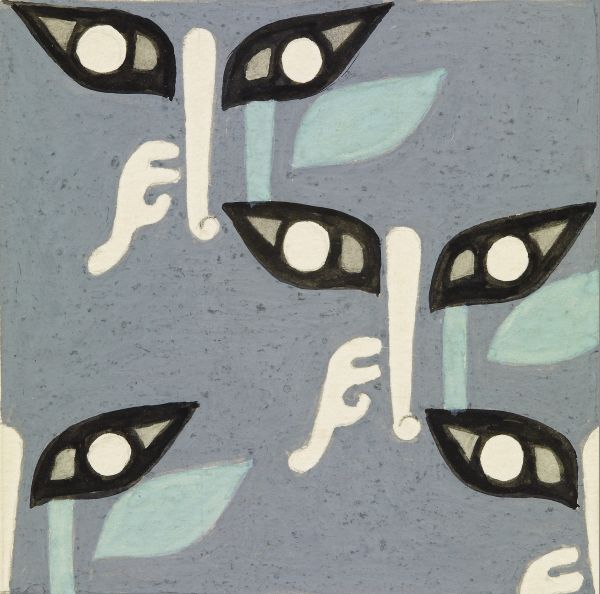

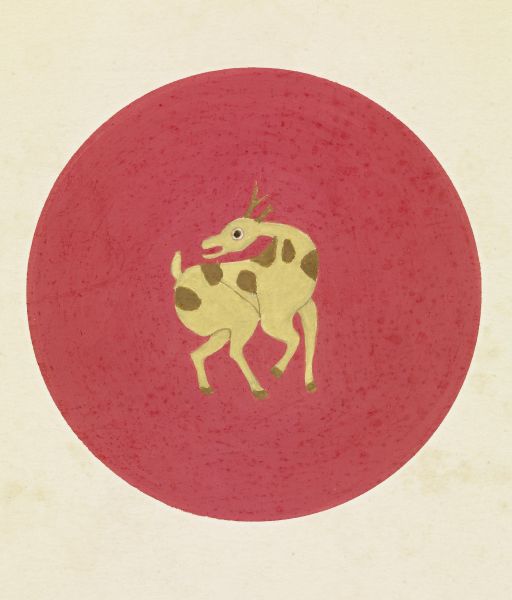

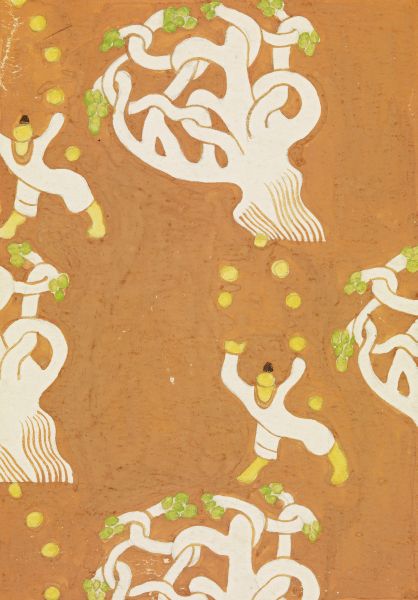

Pang Xunqin China decorative figures

Thus, by means of a particular observation of the aesthetics and thinking of Xunqin, we can appreciate the richness of the eighty-four pieces that comprise this group of artworks that has come to Valencia. They were all made in 1939, and represent a laboratory for the study and analysis of the globalised trends that arose in China over seventy years ago. In this sense I think it is interesting to point out that systematic modernity, speaking in both economic, ideological and cultural terms, did not make its appearance in China until the late nineteen eighties. However, the debate about the confrontation of the cultural differences between the Orient and the Occident arose in the 17th century, when Chinese painters started to notice the ideas of the West about pictorial representation. The spread of the political and economic imperialism of the western powers at the end of the 19th century brought about a little cultural revolution in China, where an intellectual elite appropriated a series of models from western culture and used them to give new life to their traditions. This project evolved over almost the whole first half of the 20th century, so Pang Xunqin can be placed within this period rich in cultural and artistic interrelations. With this exhibition, twenty-five years after Xunqin’s death, we reveal some of the keys to the success of an artist who studied fine arts in Paris back in the twenties. This close relationship he had with the capital of France aroused in him a strong interest in the Art Nouveau movement that lasted throughout his professional career. We can say that one of the greatest achievements of this artist and decorator was to renovate traditional Chinese decoration by incorporating elements that placed it in the context of modernity. In these almost one hundred small-format works on paper we can see how Xunqin adopted an aesthetics he discovered in the West and combined it with the patterns, images and documents he retrieved from the ancient culture of his ancestors. In this way, we find imagery full of dragons, horses, birds and other animals taken from the legendary tales of the East that acquire spectacular vividness thanks to the refreshing addition of Occidental aesthetics sometimes reminiscent of Pop artists like Keith Haring (it is worth remembering that both Xunqin and Haring put their designs at the service of the leisure, textile and household goods industries). In this sense, as we can see in this exhibition, in spite of the fact that the works were made in 1939, they are extraordinarily up-to-date. And we can say that the result of these pieces has been continual experimentation within different sorts of artistic trends, among which we can find not only the heirs of the most traditional and figurative styles but also the most abstract, conceptual and modern. There can be no doubt that to make these drawings the Chinese artist not only used his imagination and his renovating skills and, above all, an intelligence that permitted him to combine, very aptly, all his artistic resources, but he must surely have been familiar too with some of the writings from the pens of artists like Paul Klee or Wassily Kandinsky (published by the Bauhaus) and which served as an introduction to the grammar of visual writing. So, in this same order of ideas, Xunqin’s works can involve as much writing as drawing, so that their lines can be perceived, as we can see in this exhibition, as a gestalt: a simple form or image that aims to stimulate the spectator with an integrating and ground-breaking cultural vision.