Ignacio Pinazo

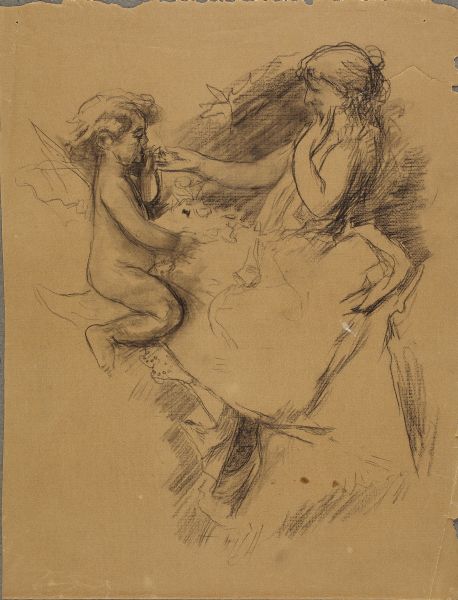

The smoke of love

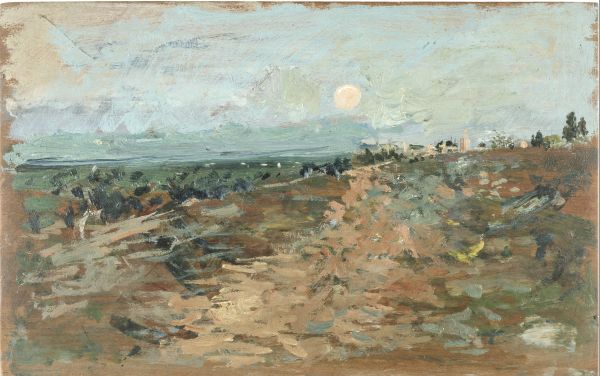

In order to reach the painting in question of Cupid lighting a cigarette, one can search for a series of antecedents and inspirations, beginning with the canvas Cazando Mariposas (Hunting Butterflies) (c. 1880) and from there to El Retrato de María Jaumandreu (The Portrait of María Jaumandreu) (1885), an allegory of springtime, and from there to the large format canvas of Bella herida por Cupido (Beauty Wounded By Cupid) (1885) (González Martí National Museum of Ceramics) which was painted on one of the decorative panels in El León de Oro bar in Valencia, which is a work of art that now proves to be another key to understanding the current exhibition. Although other paintings could be remembered and discussed, these three cited works are enough to plant the idea of the existence of an aesthetic, thematic cycle, exalting nature and the splendor of youth, the power of love and passion. Even though the selected group unites such different signature works, they act as cohesive and unifying elements of all landscapes and feminine iconography fully placed into cultural coordinates and erotic vision over the ages. Appreciating the artistic value, the psychological depth and the originality of these paintings as unique creations of their time should not be an obstacle. These are extremely well thought out and elaborate works of art in which Pinazo overturns all of his technical and compositional mastery. The scene of Cupid lighting a cigarette takes place in the middle of a springtime landscape that proclaims the earth’s fertility through the various blossoms and fruits that can be seen in the ample panorama. A natural exuberance, full of color and greenery, denoting Pinazo’s familiarity with the rural Valencian landscape. From this painting, a series of pencil and oils sketches that are represented in this selection must be emphasized as well. Pinazo tended to do numerous composition studies, namely sketches, with which he unraveled and dissected various details from the idea, repeating the same figure as many times as it came to mind. The painter tended to dissect in detail the elements of his compositions. His artwork is very elaborate and meditated, leaving nothing to chance or improvisation. The different floral and mythological-themed paintings that were made up until 1891 are also experiences that synthesize and enrich new painting. But if other details of the Cupid lighting a cigarette painting are analyzed, it can be confirmed that the woman is wearing the same dress as the woman in the large format painting on the wall of the El León de Oro bar in Valencia that represents Beauty wounded by Cupid. In the bar painting, Cupid, who also has butterfly wings, shows his quiver full of arrows. On the contrary, the smoking Cupid’s quiver is completely empty; he is unarmed and defenseless. The theme is definitely a fantasy in which a precise or logical understanding cannot be drawn from it because of its capricious and arbitrary manner, but the cited work participates with many connotative and symbolic components and elements of painting among the ages, not exempt from a certain perversity; ambiguous and metaphorical games that center around the beginning of pleasure or the ambiguity of the relationship with the beautiful fin de siècle. Beauty wounded by Cupid gives signs of a state of restlessness and longing, common of someone who has fallen into the trap of Love’s ardent fires. The elegant, nineteenth century young woman appears lying on the grass of a lush landscape. The young girl is accompanied by a mischievous Cupid with butterfly wings, who is shaped by free and expressive strokes. Cupid, a hunter who gloats upon seeing wounded prey, observes how his victim vividly suffers the effects of his arrows. The painting is an allegory of love, or more precisely, of passion and Love’s rapture, the fervor of carnal love. The woman adopts an attitude of receptive postration, a delivery eager to reveal her own postures and gestures. This makes it a very expressive painting about the interest in the awakening of thinly-veiled eroticism in the most advanced art of the period. The Smoke of Love, not as an emanation of the cigarette that Cupid smokes, but instead as a metaphor of the sensual fervor that triggers the fire of his arrows, acts as a link between other paintings in which Venus’s son is still present in some way. Pinazo’s iconographic universe was very rich and diversified. Despite his preference for a series of specific themes such as landscapes and paint types, his decorative painting and his way of developing it does not become less curious. These types of commissions are especially staggered between 1887 and 1900. Pinazo was not a decorative painting in the most strict and traditional sense of the word, but he addresses the issue in a personal manner, where both iconography and style are indicators of the modernity that represented his painting in Valencia.