Narrative Figuration

París 1960-1972

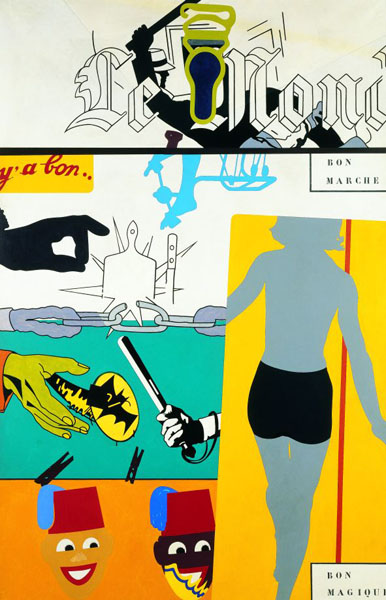

A ferocious joke wolf, a Pietà in the battle of Stalingrad, the riot police carting off a Dubuffet, the assassination of Marcel Duchamp and a painting riddled with bullet holes – all arranged in a cleverly orchestrated ambience of scandal. The emergence of New Figuration was brutal and explosive. It brought together some of the best European painters who had gone to live in Paris in the sixties, artists who produced outspoken painting that captured the spirit of the times, making full use of everyday images generated by consumer society. They thumbed their noses at good taste, moderation and elite culture and launched into a game of massacres, combining references to great paintings with denunciations of dictatorships and playful interpretations of detective stories, women’s magazines and comics. They abandoned the solitariness of the studio to seek inspiration on the street corner. Their paintings brimmed over with humour and mockery, exploiting anecdotes, strip cartoons and History with a capital H, and forty years on they have lost none of their impertinence and power. The exhibition Narrative Figuration. Paris 1960–1972 features works by some twenty artists active in the sixties, who used pictures taken from the press, advertising, comics and films to present objects, people and situations. This trend, variously described as New Figuration, Critical Figuration and finally Narrative Figuration, never produced a manifesto, but it found expression in many exhibitions, the most famous one being Mythologies quotidiennes in 1964, in which the shared concerns of the artists represented marked a raising of consciousness. The repetition of images, themes and narrative techniques taken from mass culture at the height of the enthusiasm of France’s “thirty glorious years” indicated a return to pictorial themes that contrasted with the dominance of abstract art. The desire of these artists to establish a critical political debate about society distinguishes them from observational art, such as the Pop Art and New Realism movements in those years. The artists formed groups, met in regular events (the Salon de la Jeune Peinture which reorganized around Aillaud, Arroyo and Cueco), or in connection with magazines such as KWY (Bertholo, Castro, Voss), sometimes linking up with other movements such as the Surrealists (Télémaque) or the New Realists (Bertini), and they exhibited at most of the Paris galleries, such as Daniel Cordier, Mathias Fels and Carlota Charmet. In Paris, ARC (Animation Recherche Confrontation), a structure set up by Pierre Gaudibert in the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1967, presented the first monographic studies in the museum. The artists were defended by critics such as Gérald Gassiot-Talabot, Jean-Jacques Lévêque and Alain Jouffroy and art journals such as Opus International. The patterns evolved as time went by: a shift from abstraction towards figurative art in the early sixties, drawing inspiration from everyday images; political commitment from 1962 to 1975; and, finally, a more individually focused, poetic, metaphorical questioning of objects towards the end. These artists took up positions totally at odds with the tradition of “beautiful painting”. Revolutionaries following in the footsteps of Surrealism, originating from all parts of Europe and arriving in Paris at the very moment when New York was becoming the capital of live art, they sought to use narrative to find new sources of images. Caught between the last sparkle of Paris School abstraction and the steamroller of American Pop Art, they have not always received their due recognition on an international level. The show presents about a hundred of the most outstanding paintings produced between the early sixties, when these European artists settled in Paris, and the exhibition presented at the Grand Palais in 1972, 60/72: douze ans d’art contemporain en France. One section of the exhibition is devoted to the beginnings and to Mythologies quotidiennes, and then there is an exploration of other sources of inspiration: the clear, forceful aesthetics of comics, the re-examination of art history, and the fantasies of crime thrillers. The exhibition ends with works in which political commitment is prominent. The show occupies three of the IVAM’s galleries and is divided into six sections. It starts in Gallery 4 (2nd floor), with areas devoted to the beginnings, the Mythologies quotidiennes exhibition, comics, objects, and the shift away from classical painting. The sections that focus on crime thrillers and politics are in Gallery 7 (2nd floor) and Gallery 8 (1st floor).