Christian Stein’s Collection

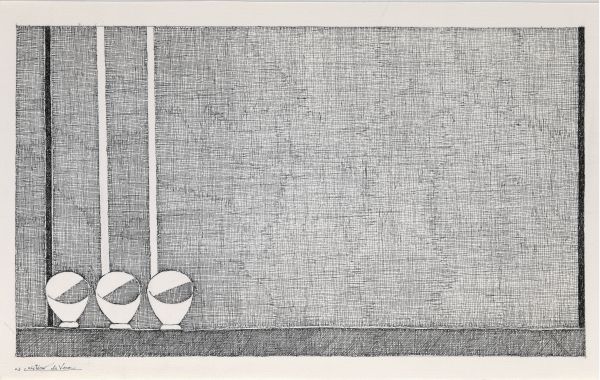

A twofold task: mourning for the loss of the heroism that the avant-garde had once claimed for art; and furious experimentation with forms and gestures that invaded the various scenarios of those years and that now occupy a privileged position in this exhibition of works from the Christian Stein Collection. Italy was undoubtedly one of the main European settings in which those economic, political and social transformations and the corresponding cultural processes of resistance took place. The particular political and ideological conditions that prevailed in Italy at the time, exposed to an accelerated process of industrialisation, elicited responses that may now be considered an essential reference for any history of the culture of the latter half of the twentieth century. Indeed, it was the tensions between the elements that constituted the dominant traditions that led to the emergence of discourses and proposals, now identified by names such as Arte Povera or Radical Architecture, that were veritable laboratories of European culture. A long journey of exploration of artists such as Boetti, Paolini, Mario and Marisa Merz, Luciano Fabro, Pistoletto and Kounellis, not forgetting Penone, Zorio, Anselmo and others, might now be the best way to approach an artistic experiment that transcends the coordinates of the forms of art and affects the strategies of culture and political forms, which in turn have their impact on the increasingly complex structures of the social and of relationships between private and public, marking the line of emergence of new individualities. If the fronts opened up by Calvino and Pasolini, to cite just two examples, proposed experimenting with the very concept of literature or making a more direct criticism by unmasking the cultural and religious fetishisms of Italian society, Arte Povera also constructed a dramaturgy in which there was a representation of changes in a society that had lost its traditional system of references and found itself exposed to a new system of regulation and redirection to a new world of social imagery in an international context dominated by the model of post-industrial societies. Fontana’s slashed canvases, Kounellis’s oxides, Paolini’s broken mirrors, Luciano Fabro’s attaccapanni (hangers) and Alighiero Boetti’s maps explore a geography of signs and scenes in which there is a representation, as if in a theatre of time, of the new social relationships or the impossible journey towards an age that once was dreamed of. It was Goethe who said, in his notes on Winckelmann, that “classicism is the sense of nostalgia for home”. There was no way back, and the work of art and the new aesthetic ideas assimilated the changes of the age from a critical distance that invented new languages which emerged from the utopian tension that an ethical and political rebellion demanded and that the works of the Christian Stein Collection interpret.