Francis Bacon

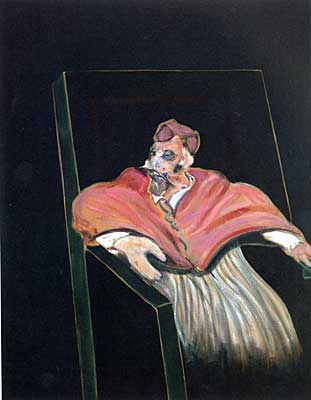

Every important exhibition of Francis Bacon’s work, both during his life and since his death in 1992, has been a retrospective. The great, early tributes organized by the Tate Gallery (1962), the Grand Palais (1971-72) and the Metropolitan Museum (1975) had a distinct raison d’être because they allowed a wide public to discover the breadth and intensity of Bacon’s inventiveness as an image-maker. But the trend has continued unchanged over the last quarter-century, with dozens of museums, from Tokyo and Minneapolis to Dublin and the Hague, following in the footsteps of their predecessors and aiming to present as complete an overview as possible of Bacon’s work, with every theme and period represented. The result is that there is now a well-established, not to say “official”, way of looking at what was once the artist’s immensely disturbing, rebellious and anarchic achievement. The aim of the present exhibition is to reverse that unquestioning tendency and to look at Bacon anew by focusing solely on a single theme that haunted the artist for over twenty years: the “Pope” pictures. By bringing together the whole series of paintings and restoring them to the context in which they were made, we hope to make more apparent the range of ambition, risk, intuition, unconscious impulse and despair that drove the relatively young and unknown Francis Bacon to make this unprecedented assault on one of the great icons of Western art and civilization. Bacon had been haunted by the power and beauty of Velázquez’s Retrato de Inocencio X (Portrait of Innocent X) for years before he painted Head VI, his first recognizable version of the picture, in 1949. He considered the Spanish master’s portrait to be one of the greatest images in all Western art and he had, in his own words, become “obsessed” with it. Reproductions of the famous painting, mostly in black and white, were pinned to his studio wall or scattered in the chaos of photographs and artist’s materials that littered the floor. At one point, Bacon likened his fascination with this particular image to a “crush” —the kind of semi-erotic hero-worship a young boy may develop for an older, more important pupil at school. This curious love affair dominated Bacon’s painting life for over twenty years, from 1949 until the early 1970s; and it was not until 1971, when he completed a second version of Study for Red Pope was his obsession with Velázquez’s portrait finally worked through and abandoned. At that point Bacon had executed a good forty paraphrases of the Spanish masterpiece (or considerably more, if one takes into account the numerous versions which the artist abandoned or destroyed). Why did the “Pope” theme so captivate Bacon, causing him to make more variations on it than any other subject in his entire career? For what reason, out of the thousands of photographs and reproductions he kept in the chaos of his studio, did he return time and again to this one portrait by Velázquez? How did this constant paraphrase allow the artist to express deep-seated conflicts and urges that could not otherwise have been conveyed? What other sources informed this extraordinarily potent sequence of images? And, above all, why did the militantly and outspokenly atheistic Bacon cling so tenaciously to an image of religious significance? These are some of the questions we hope to be able to examine in depth by bringing together for the first time the forty variations on the theme of the Pope that Bacon painted between 1949 and 1971. What makes this whole series —and the aesthetic questions it raises— so fascinating is that it allows one to follow Bacon through a long period of almost constant mutation. Virtually every visual source that had interested him found its way into these ambiguous and highly suggestive images, changing their impact in unexpected ways. Clearly, there was Velázquez’s original model, the icon which Bacon both revered and desecrated. But there was also the still of the screaming nurse from Eisenstein’s Bronenosets Potyomkin (El acorazado Potemkin), Muybridge’s sequential photography and other famous pictures such as Titian’s half-veiled Ritratto di Filippo Archinto (Portrait of Filippo Archinto). Photographs of Eichmann on trial in his glass cage and of dictators haranguing their audience or animals baring their teeth also played a part. These are amongst the best-known sources. But Bacon drew on an extraordinary range of visual, literary and other stimuli. As he once said: “Don’t forget, I look at everything and it all gets ground up very fine.” And new sources for his imagery have been discovered very recently in the countless photographs and books that Bacon left strewn across his studio floor when he died. For Bacon, the Papal image presented almost infinite possibilities for association and metamorphosis. His great ambition as an artist was to create images that could spark off sequences of other, apparently unrelated images, thus opening what he liked to call “the valves of the imagination”. Moving from one version of the Pope to the next, Bacon gave free rein to stray impulse, allowing “the great well of images” he carried within him to surface into the work in hand and suggest new forms with constantly changing implications. To study the whole sequence of the Popes, painted while the artist was at the height of his powers, is to go to the heart of Bacon’s extraordinary achievement.